The word “seraphim” is often associated with angels, but its origin and meaning are more complex and mysterious. In this article, we will explore the historical evolution of the concept of seraphim from the ancient Near East through the Bible, and see how these beings transformed from winged serpents to heavenly singers.

The Meaning of Seraphim

The word “seraphim” is the plural form of the Hebrew word saraph, which means “to burn” or “to destroy”. The word is used in the Bible to refer to various kinds of fiery creatures, some of which are serpentine in form. For example, in Numbers 21:6-8, God sends “fiery serpents” (hhannehasim hasserapim) among the Israelites as a punishment for their complaints.

Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. So the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, because we have spoken against the Lord and against you; intercede with the Lord, that He will remove the serpents from us.” And Moses interceded for the people. Then the Lord said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent, and put it on a flag pole; and it shall come about, that everyone who is bitten, and looks at it, will live.

– Numbers 21:6-8 (NASB)

God then instructs Moses to make a bronze serpent (nehushtan) and set it on a pole, so that anyone who is bitten can look at it and live.

The word saraph is also used in Deuteronomy 8:15 and Isaiah 30:6 to describe the dangerous animals that inhabit the desert.

He who led you through the great and terrible wilderness, with its fiery serpents and scorpions, and its thirsty ground where there was no water; He who brought water for you out of the rock of flint.

– Deuteronomy 8:15

The pronouncement concerning the animals of the Negev:

– Isaiah 30:6 (NASB)

Through a land of distress and anguish,

From where come lioness and lion, viper and flying serpent,

They carry their riches on the backs of young donkeys,

And their treasures on camels’ humps,

To a people who will not benefit them;

In some cases, the word saraph is modified by the adjective “flying” (me’opep), which may indicate the swift movement of the snakes or their ability to leap or glide. In Isaiah 14:29, the prophet uses the image of a flying serpent (sarap me’opep) as a metaphor for a new enemy that will arise from the ruins of Babylon. The word “flying” may also suggest a connection with the sky or the divine realm, as we will see later.

The Origin of Seraphim

The origin of the concept of seraphim is not clear, but it may be related to the Egyptian uraeus serpent, a cobra figure that was worn on the forehead of Egyptian gods and kings as a symbol of protection and power. The uraeus serpent was believed to spit fire at the enemies of its wearer. The uraeus motif was well known in Palestine from the Hyksos period (ca. 1650-1550 BCE) through the end of the Iron Age (ca. 586 BCE), as evidenced by various scarabs and seals that depict winged or multi-winged uraei.

Another possible source of inspiration for the concept of “seraphim” is Mesopotamian mythology, where serpentine beings are often associated with thunder and lightning. For example, in the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic, the god Marduk defeats the primordial dragon Tiamat and her allies, who are described as “sharp-toothed serpents” (mušhuššu) and “venomous dragons” (bašmu). Marduk then uses Tiamat’s body to create the heavens and the earth, and places her eyes as sources of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In another myth, Marduk slays another dragon called Mushussu, who is depicted as a hybrid creature with a snake’s head, a lion’s body, an eagle’s wings, and a scorpion’s tail. Marduk then takes Mushussu as his emblem and mounts him on his chariot.

The Transformation of Seraphim

The most famous and influential depiction of seraphim in the Bible is found in Isaiah 6:1-7, where the prophet has a vision of God’s throne surrounded by six-winged beings who sing praises to God and purify Isaiah’s lips with burning coal. These beings are called seraphim, but they are very different from the fiery serpents mentioned earlier. They have human-like faces, hands, and feet, and they use two wings to cover their faces, two wings to cover their feet, and two wings to fly. They are not hostile or harmful, but rather benevolent and helpful. They are not associated with fire or destruction, but rather with holiness and purification.

How did this transformation happen? There are several possible explanations. One is that Isaiah reinterpreted the existing concept of “seraphim” in light of his own experience and theology. He may have been influenced by other biblical passages that describe God’s throne as surrounded by winged creatures, such as Ezekiel 1:4-28 and 10:1-22, where God’s chariot is carried by four living beings with four faces and four wings each. He may have also been inspired by other Near Eastern iconography that depicts divine or royal figures flanked by winged attendants, such as the Assyrian reliefs of Ashurnasirpal II and Sargon II. Isaiah may have used the word “seraphim” to emphasize the fiery and majestic nature of God‘s presence, but he also modified their appearance and function to suit his own message.

Another explanation is that Isaiah adapted the concept of seraphim from the Canaanite or Phoenician mythology, where Baal and Anat were prominent deities. Baal was a god of storms, fertility, and kingship, who wielded a thunderbolt and was called “the rider on the clouds”. Anat was a goddess of war and love, who was sometimes depicted as a winged lioness or a winged sphinx, and who fought fiercely for Baal’s cause. Isaiah’s vision of seraphim may reflect a polemical adaptation of Baal and Anat imagery, where the prophet replaced the pagan deities with Yahweh and his servants.

A third explanation is that Isaiah’s vision of seraphim represents a synthesis of various traditions and influences, both biblical and extrabiblical. Isaiah may have combined elements from different sources to create a unique and original vision that expressed his own understanding of God and his relationship with his people. Isaiah may have also intended to convey a sense of mystery and awe, by using a word that had multiple meanings and associations, and by describing beings that were both familiar and unfamiliar, both human and non-human, both earthly and heavenly.

Seraphim In Enoch & the New Testament

The concept of the seraphim did not end with Isaiah but continued to develop and evolve in later Jewish and Christian literature. In the pseudepigrapha, such as 1 Enoch and 2 Enoch, the seraphim are described as one of the highest orders of angels, along with the cherubim and the ophanim. They are said to be “the sleepless ones who guard the throne of God’s glory” (1 Enoch 71:7). They are also involved in various heavenly activities, such as singing praises, interceding for humans, delivering messages, executing judgments, and fighting against evil.

In the New Testament, the seraphim are not mentioned by name, but they may be alluded to in some passages that refer to angels or heavenly beings. For example, in Revelation 4:6-8, John sees four living creatures around God’s throne, each with six wings and covered with eyes. They sing “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty, who was, and is, and is to come”. These creatures may be based on Isaiah’s vision of seraphim, or on Ezekiel’s vision of living beings, or on both.

And the four living creatures, each one of them having six wings, are full of eyes around and within; and day and night they do not cease to say,

“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God, the Almighty, who was and who is and who is to come.”

– Revelation 4:8 (NASB)

In Hebrews 1:7, the author quotes Psalm 104:4 and says that God “makes his angels winds [or spirits], his ministers a flame of fire”. This may suggest a connection between angels and seraphim since both are associated with fire.

Seraphim in Later Christian Traditions

In later Christian traditions, the seraphim are often regarded as the highest rank of angels, surpassing even the cherubim in glory and closeness to God. They are usually depicted as human-like figures with six wings and radiant faces. They are also associated with love, wisdom, light, and fire.

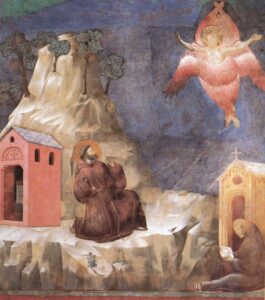

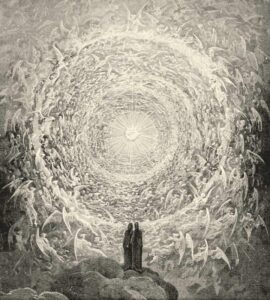

Some famous examples of seraphic imagery in Christian art and literature are Dante’s Paradiso, where he sees nine circles of angels around God’s throne, with the seraphim being the innermost circle; Fra Angelico’s frescoes in San Marco monastery in Florence, where he portrays various saints as seraphic figures; and Francis of Assisi‘s stigmata, where he receives wounds on his hands, feet, and side from a vision of a six-winged seraph.

The term “seraphim” reflects the diverse and dynamic meanings and representations of an ancient concept over time. Depending on the perspectives and purposes of different authors and artists, these beings have undergone various transformations. They have changed from winged serpents to heavenly singers, from adversaries to allies, from guardians to devotees, and from emblems of authority to emblems of love.

References:

- Day, John. “Echoes of Baal’s Seven Thunders and Lightnings in Psalm XXIX and Habakkuk III 9 and the Identity of the Seraphim in Isaiah VI.” Vetus Testamentum, vol. 29, no. 2, 1979, pp. 143-151.

- Lederman, Richard. “The Seraphim.” TheTorah.com.

- New American Standard Bible. Updated Edition, The Lockman Foundation, 2020

- Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Smith, Mark S. “The Near Eastern Background of Solar Language for Yahweh.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 109, no. 1, 1990, pp. 29-39.

- Toorn, Karel van der, et al., editors. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Brill, 1999.

- Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic, 2006.

Genesis and Enuma Elish: A Comparative Analysis of Two Creation Stories

Genesis and Enuma Elish: A Comparative Analysis of Two Creation Stories